Although in the past few decades Zemun is best known for its tough guys (read: mafiosi), great lively restaurants a more chilled vibe than old Belgrade, this ancient town has for centuries been a vibrant melting pot of various cultures, drawing merchants and craftspeople to the border of Central Europe and the Orient, which, for centuries lay on the banks of the Danube.

Despite many churches serving various faiths (from Belgrade’s only Franciscan monastery to a modernist protestant rotunda), Zemun’s multicultural roots have been almost severed due to mass shifts of people during and after WWII. Its only remaining synagogue was converted in 1990s into (admittedly very good) Serbian ‘sac’ restaurant, which now operates with consent of the Serbian Jewish community, with the hope that the space will be converted into something more kosher in the near future.

It is close to here, in Zemun’s old Jewish ghetto, that in 1825, a 27-year-old Sephardi scholar from Sarajevo, Judah Alkalai (or Jehuda Alkalaj in Serbian), came to preach, after having been educated in the matters of faith and Kabbalah in Jerusalem. Back then, Zemun (or Semlin) was a town of about 5,000 inhabitants in the Military Frontier of the Habsburg empire, and its inhabitants, besides Serbs, also counted Germans, Croats, Slovaks, Armenians and Jews.

In 1820s, Zemun’s Jewish community was centred around the present-day Dubrovacka street (then Jewish Street). It counted about a few hundred people and was a mix of Ashkenazi from all around the Habsburg lands who came to enjoy the town’s good trading position, as well as Sephardi who were escaping the increasingly crumbling and chaotic Ottoman rule in Bosnia and present-day Serbia. Among them there was a number of Sephardi from Serbia escaped the tumult of First Serbian uprising (1804-1813), and brought the tales of Serbian struggle for national independence and own state.

Precarious position of Jews in both the Ottoman and Habsburg Empire and the awareness of the national self-determination movements steered the young Rabbi towards activism for Jewish rights and proto-Zionist ideas. In 1839, Alkalai’s first book, Darhi noam (The Pleasant Paths), was printed by “Princely Press” (Knezeva stamparija) in Belgrade and it contained first of his many incitements for Jews to move to Palestine.

Alkalai’s worries about security of Europe’s Jews were further spurred after an 1840 incident in Damascus, when its Jewish community was attacked after accusations of murdering a Franciscan monk, and only saved after interventions by a prominent Jewish financier Moses Haim Montefiore.

This meant that he not only continued with his publishing and activism, but also formed the first in the series of many short-lived societies for settlement of Palestine, “Erez Yisrael”, which operated in Zemun, Belgrade and Šabac. Although these did not prove successful, he decided to try his luck on a grander scale. Throughout 1850s he travelled around Europe, trying to persuade Jewish communities to support his plan, but he failed to conjure enthusiasm for his grand plans, which included collection of tithe from Jews around the world to finance resettlement, and petitioning the sultan to grant the same status to Jews as was granted to Serbia, Moldavia and Wallachia.

Although his frequent travels around Europe almost bankrupted him it was a connection with another Zemun family that will probably prove crucial for the future of Jewish settlement of Palestine.

Simon Leib Herzl, a fellow Zemunian, was a keen attendee of Alkalai’s sermons and is thought to have been married by Alkalai. He was then assumed to have transmitted Alkalai’s ideas to his son, Jakob’s family in Budapest.

Luckily for Alkalai, one of Simon’s grandsons, was none other than Theodor Herzl, who was to become the founder of the Zionist movement after being a liberal assimilationist in his youth. Although the direct link between the two is not fully corroborated in scholarship, the basic similarity of their ideas, as well as the link though Theodor’s family in Zemun, make it very likely that Herzl’s Zionist ideas were at least in part, inspired by Alkalai’s preaching.

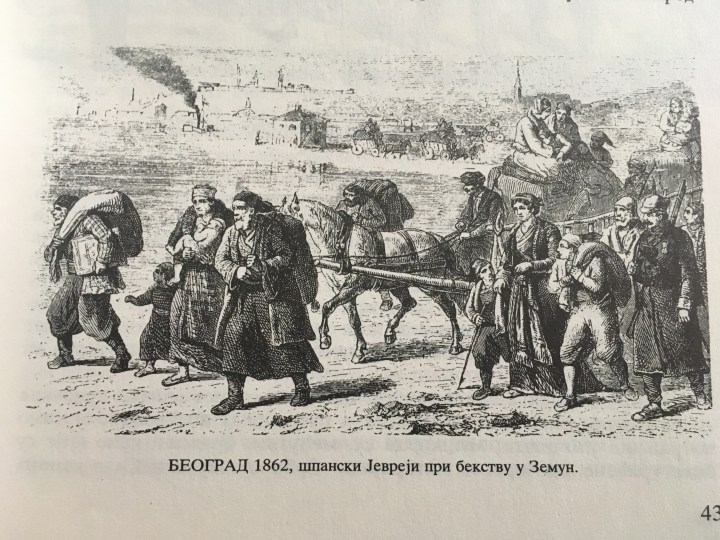

However, much before the 1894 Dreyfus affair turned Herzl towards Zionism, busy rabbi Alaklai experienced improved station of his community. Firstly, Jews were allowed free settlement across Zemun (and the empire it belong to) from 1862. The town received a first Ashkenazi synagogue (which still stands), and in 1871, a beautiful neo-gothic Sephardi synagogue was built (destroyed during WWII). In the same year, Alkalai visited Jerusalem to found yet another of settlement societies, only to move there permanently in 1874 with his wife. He stayed there until his death in 1878 and is buried at the Mount of Olives Jewish cemetery.

Alkalai’s and Herzl’s idea of independent Jewish state remained were supported by the Serbian (and later Yugoslav) Jewish community and Serbia itself. Indeed, Serbian government in exile was the first to support the Balfour declaration, an initiative by the British government supporting the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Ottoman-held Palestine in 1917. This was thanks to the efforts of the prominent Serbian Jewish military officer, physician and diplomat David Albala.

Zemun’s Ashkenazi synagogue, discernible by the stylised representation of tablets bearing 10 commandments and an inscription in Hebrew, Jewish part of the Zemun cemetery (which still holds the remains of Simon Herzl and his wife), Rabbi Alkalai street, and the new street named after Theodore Herzl are now the reminders of Zemun’s prominent if smallish Jewish community. The community itself, which counted 585 in 1940, mostly perished when the city was annexed by the Independent State of Croatia in 1941 and many of those who survived the Holocaust, decided to leave for Israel.

One thought on “Hidden Belgrade (34): Rabbi Alkalai, Zemun and Zionism”