In this year of many big anniversaries – 80 years since the beginning of WWII in Serbia, 60 years since Ivo Andrić received the Nobel Prize for „The Bridge over the Drina“ – there is a strange silence about one of the most interesting event in Serbian culture which now celebrates its 50th anniversary: the 1971 Congress of Cultural Action n Kragujevac.

The Congress is an under-appreciated, if not openly hushed up, event in Serbian cultural history, but also an interesting case study in the Cold War approach to cultural policy, rife with political intrigues, such as using high culture as ideological propaganda, documented in Frances Stonor Saunders’s “Who paid the piper”.

The Congress, was the largest gather of Serbia’s cultural elite, organised by the Serbian socialist top brass, in order to try to set the course for Serbian culture, and set it towards ever greater heights.

It was organised during a major boom in cultural production and literacy in Yugoslavia, a country which was nicely placed in the middle of the two Cold War blocks, and enjoyed cultural overtures from both. Indeed, Yugoslavia’s Non-Aligned position, was key in the country become a meeting place between Western and Warsaw-pact cultural productions, and the many large festivals founded in 1961 – FEST, BITEF, BEMUS – were one of the few in the world where artists from both blocks would meet. Belgrade, famously, had the first European production of Hair in 1969, and was a stop for many foreign touring exhibitions. Most importantly, its cultural market was open to (mostly Western) foreign mass cultural products like films, comics and erotica, which on occasions clashed with the ethos that was supposed to be promoted in a socialist country.

Thus, it was seen as necessary to thing and plan what is to be done to harness the immense power of popular culture in the country.

Kragujevac was chosen on the insistence of Latinka Perović, the second in command among Serbia’s communists and the head organiser of the congress, a native of the city and, despite the obvious local patriotism of the organiser it was a sensible choice. The city was not only a former Serbian capital, nestled in the heart of Šumadija, but it was also a socialist industrial city par excellence – the first Serbian factory was founded there in late 19th century and it was the heart of Yugoslav automobile industry – and also a city whose population was massacred in 1941 by the Germans as a reprisal for early resistance to their occupation of Serbia and Yugoslavia.

The congress was hosted inside the Šumadija hall, built in 1968 (now, sadly, almost in ruins) and it drew all the luminaries of the Serbian cultural scene.

The first among them was Ivo Andrić, who received a Nobel prize for literature a decade before the congress which served as a sign that the Yugoslav culture could stand shoulder to shoulder with other great global cultures, but there was also the architect, and future mayor of Belgrade, Bogdan Bogdanović, philosopher Radomir Konstantinović, poet Oskar Davičo, the famed actress Mira Stupica, and, interestingly, Milena Dravić the star of Makavejev’s WR Mysteries of Organism, which was banned in Yugoslavia in May that year. Besides them, there were the political commissars from Serbia: the Chairman of the League of Communists of Serbia Marko Nikezić and Ivan Stambolić.

The only one who boycotted the Congress was the writer and Perović’s arch nemesis, Dorbrica Ćosić, then head of the publisher Srpska Književna Zadruga (SKZ, Serbian writer’s guild) Serbia‘s oldest writers’ organization and one of the oldest and most estreemed publishing houses in the country. According to Perović, in early discussions about the event SKZ’s representatives „thought that [the Congress] was not a true opening [of the Party] to the intelligentsia and to culture, that it was a bureaucratic manipulation and that they would not participate in such manipulations“.

The congress opened with Perović’s now infamous introductory speech she stated the goals of the Congress as well as her view of the state of Serbian culture using tropes which still survive to this day: “In a society still characterised by economic underdevelopment, low level of civilisation, unenlightenment and cultural backwardness – democratization of culture will be of great value for long-term achievement of elementary literacy, mass education availability of cultural goods to the widest social strata, urbanization of villages and cleanliness of our cities.”

Interestingly the “democratisation of culture” she mentioned, did not mean cultural populism but exactly the its opposite. Not only was one of the main aims of the congress purging the socialist culture of kitsch, exemplified in popular genres and cultural products from comics and erotic novels to pornography and ethno-infused music (which later evolved into turbofolk), but it was also establishing of the full control over artistic expression through bureaucratisation of creativity in the guise of fighting against subversion of state power, by fighting against “conservatism” and “nationalism” (due to their popular appeal, as seen during the Croatian Spring). Perović continued with a few sentences which will lend her in hot water later:

“The question of institutions in culture, science, education is also raised. It’s not about their

needs, but about their orientation. Conservatism is no less or more of a rule in them than it is in the wider society. That is why the solution is not only to banish conservatism, but to create space for something new. It is said that it is not enough to bury the old gods, a world should be created in which they will not be able to live.”

The strangeness of raising to fight against “conservativism” of institutions while one is a head of Secretary of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Serbia, which has, by then, been in power for 26 years is only highlighted by the fact that it was not only “conservative” subversion and kitsch that the Party liberals cracked down on but also on people like Dušan Makavejev, whose extremely innovative film was banned a few months before the Congress. What the aim of the congress was is to legitimate the power over culture and ability to police peoples tastes on a whim, under the guise of protecting them from “the mass market”.

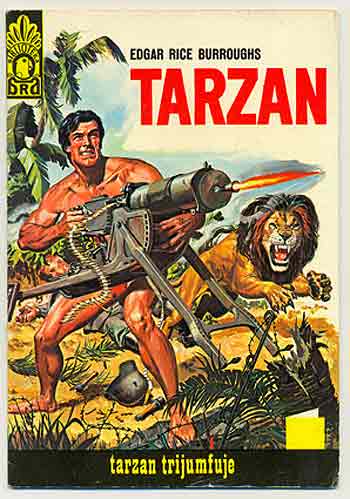

The potential for excesses of such view of culture and society demonstrated themselves on the first eve of the Congress, right outside Šumadija hall. A group of Communist youths, organised a bonfire of “kitsch”, allegedly with no guidance from the party grandees or connection of the organisers of the Congress. Carrying placards decrying kitsch and praising high culture, they set comics like the Tarzan and erotic magazines alight.

Once it was time for Perović and Nikezić to take the fall a few months later for being “anarcho-liberals”, this sacrificial offering of printed material drew unflattering, but obvious, comparisons to Nazi pyres of books and degenerate art.

However, while Nikezić, Perović and their allies were wiped out from the top brass of the Communist party, the attitudes towards the arts and cultural policy promoted at the Congress not only lingered among Serbia’s elite, but were codified.

In the immediate aftermath, a “tax on kitsch” was implemented on the publications and art forms (comics, “light” novels, especially), to nudge the population towards more high-minded production. While traditional folk music, performed by dwindling folk societies was encouraged, “novokompnovana” genre of music, which covered newly composed, and often lyrically and musically “updated” traditional music became synonymous with bad taste and came to occupy the same low place in the elite worldview in the same way its descendant, turbofolk did in 1990s.

The direct consequence of these policies was stifling of the boom in creativity in Serbian comics and entertainment publications, which closed, as the public in Serbia reached out for cheaper alternatives from other republics and abroad. While many of the stars of “novokomponovana”, such as Toma Zdravković, Šaban Šaulić, Sinan Sakić and others are now considered as “classical” performers and even celebrated by the current Serbian elite, their work was vilified for decades although they managed to earn more than a good income from their catchy tunes (in a lot of ways thanks to the large diaspora, which was unaffected by the cultural snobbery at home).

Serbian official pop culture (apart from, arguably, the films and TV), became decidedly and somewhat strangely elitist, with artists jousting to secure various sinecures, protected by taste makers, rather than access the market. Traditional art and culture, only tolerated in its most conservative forms, became ossified and distant, as any playful references and updating risked to run afoul of the rules. Ironically, consuming foreign and especially Western pop culture – whether updated folk music of Dylan, easy reading genres such as Pearl Buck or reading foreign comics –conferred a certain level of cultural prestige, despite being essentially not that dissimilar (in terms of production) to what was dismissed as harmful kitsch at home.

A little less than a decade after the congress, Serbian socialist authorities, as well as those in other republics, came to appreciate the power of populist pop culture and started harnessing it in official gathering, leading to the culturally (if not economically) golden age of 1980s. It was then that Lepa Brena and Bijelo Dugme became massive pan-Yugoslav (and pan-Eastern European) stars. Increased sense of nationhood (as Yugoslavia grew weaker) also popularised playing with the updated national motifs.

While the elitist and strict structure of cultural production suffered defeat in Yugoslavia and was not continued in any of the successor countries, it was replicated in smaller measure by certain parts of the elite (containing Perović who re-emerged as one of the harshest critics of Milošević in 1990s) who managed to draw funding from international NGOs and other foreign suppoertes to deal with “important” issues in their art.

Their stance remained firmly didactic and anti-populist as it was in 1971, and their messianic self-perception led them on to various (mostly popularly unsuccessful) projects of changing the popular taste, if not through the quality of their work, then by branding everything that was outside of their remit as, at best, kitsch and at worst, deeply ideologically problematic, “fascist”, “nationalist” and “jingoist”. The more popular the genre out of their remit, the more it attracted attention, thus “turbofolk”, one of the ironically only remaining pan-ex-Yugoslav institutions was linked directly to the tragic wars of Yugoslav dissolution in one of their more egregious projects, docu-series “Sav taj folk” (All that folk) in 2000s. It is also a common trope among Serbian cultural elite, that they decry the people as dumb for not liking their (often sub-mediocre) art, and be obsessed by giving out awards to each other.

As it happens, this ossified, controlling attitutes to cultural policy, was also a debacle in terms of communicating to what is good about Serbia. Guča, a raunchy trumpet festival, draws in more foreign visitors than any festival of locally produced art, and it is Kusturica (who ran afoul of Perović’s set) who is the most globally well known local artist.

This vignette about attempts to control creativity and culture, is not to lay blame on this set of Serbian elites in the very optimistic days of international growth. The circumstances of their era were such that people did believe that changing cultures and peoples for the better through arefully managed and engineered culture , was possible. In a lot of ways, they rode on the very strong wave of Serbian elite’s feeling of cultural inferiority which existed since the country became independent, and led it to many indetity crises, from the erasure of its Oriental culture in mid-19th century to wholehearted embrace of modernism (and communism) in the realy 20th century.

However, it does seek to show how creativity and art, if one wants them to be truly creative and wonderful, cannot be controlled, let alone manufactured, through a bureaucratic apparatus of quotas and cancellations, no matter how good the intentions.

Sources:

Vladimir Paunović’s excellent article on the congress

Trailer of his film about the Congress

History of the Serbian comic books

http://www.rastko.rs/strip/1/strip-u-srbiji-1955-1972/index_l.html#sund

The (very expensive) publication of essays from the Congress

Miša Đurković’s essay on Yugoslav pop

Radina Vučetić on the Americanisation of Yugoslav pop culture

https://ceupress.com/book/coca-cola-socialism

The Nutshell Times is an independent project and a work of love – but it still requires money to run. If you like the content you can support it on Paypal or Patreon.